A beginner’s guide to wabi-sabi

‘In a perfect world’

‘Practice makes perfect’

‘Picture perfect’

What do all these expressions have in common? They establish a concept of perfection: a finite state of being that cannot be improved upon.

The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi rejects the idea of perfection as something aesthetically pleasing or even achievable. Instead, it focuses on the beauty that can be found in imperfection through respect for nature and the passage of time.

Let’s dive in!

A Perfect Obsession

Our society has been obsessed with perfection for centuries. In the Western world especially, most of what we find aesthetically pleasing comes from a set of ideals on how things should look and behave.

Think of paintings by Michelangelo and Da Vinci, their brushstrokes masterfully blended so that not one hair is distinguishable from another. It seems as though the pieces were not painted so much as they appeared already formed.

Though our ideas of perfection have evolved with time, those artistic ideals are still ingrained in our psyche. Even Vincent Van Gogh, whose work is recognised today as one of the most influential of all time, was described by critics of his time as sloppy and amateurish. It’s not difficult to see why they might have thought that. Obsessed with colours and texture, Van Gogh’s highly visible brushstrokes were a far cry from the art world’s idea of perfection.

Now, think of a perfect beauty. Though beauty standards will change from country to country, they often have something in common: youth. An unblemished face, not yet touched by the effects of time. Billions are spent every year on cosmetic surgeries by people hoping to stop the flow time from affecting them. After all, would you still find a rose beautiful after it has withered?

With wabi-sabi, you might.

What is wabi-sabi?

“Wabi sabi is a way of life that appreciates and accepts complexity while at the same time values simplicity. It nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.”

- Richard R. Powell, Wabi Sabi Simple.

Simply speaking, wabi-sabi is a Japanese world view centred around appreciating imperfection and impermanence. It can be observed throughout all Japanese art forms.

At its core, wabi-sabi comes from two overlapping but distinct concepts.

Wabi, which has no true English equivalent, ties in ideas of humility and natural life. It started out as a somewhat insulting term but evolved with the Zen philosophy to take on a more positive meaning of calm appreciation and awe the face of what nature has to offer, as imperfect as it may seem.

Sabi refers to the passage of time and the cycle of life. It is the idea that visible signs of ageing add spiritual and aesthetic value to an object. It can be translated to ‘withered’ or ‘chill’, denoting the tranquillity and beauty in time passing.

Influenced by Buddhist ideas and artistic movements over centuries, wabi and sabi eventually evolved into a single concept of flawed beauty. A certain wistful melancholy brought on by nature putting the final touch on a man-made piece of art.

A few examples

One aspect of wabi-sabi is to treat damage to an object as part of its history, rather than as something shameful that must be hidden. Through visible acts of repair, the broken parts are enhanced and put forward, which gives the object more personality than it had when it was whole.

Two of the main art forms linked to this concept are kintsugi and sashiko.

Kintsugi consists of repairing broken bits of pottery with a gold lacquer to strengthen and embellish the broken object.

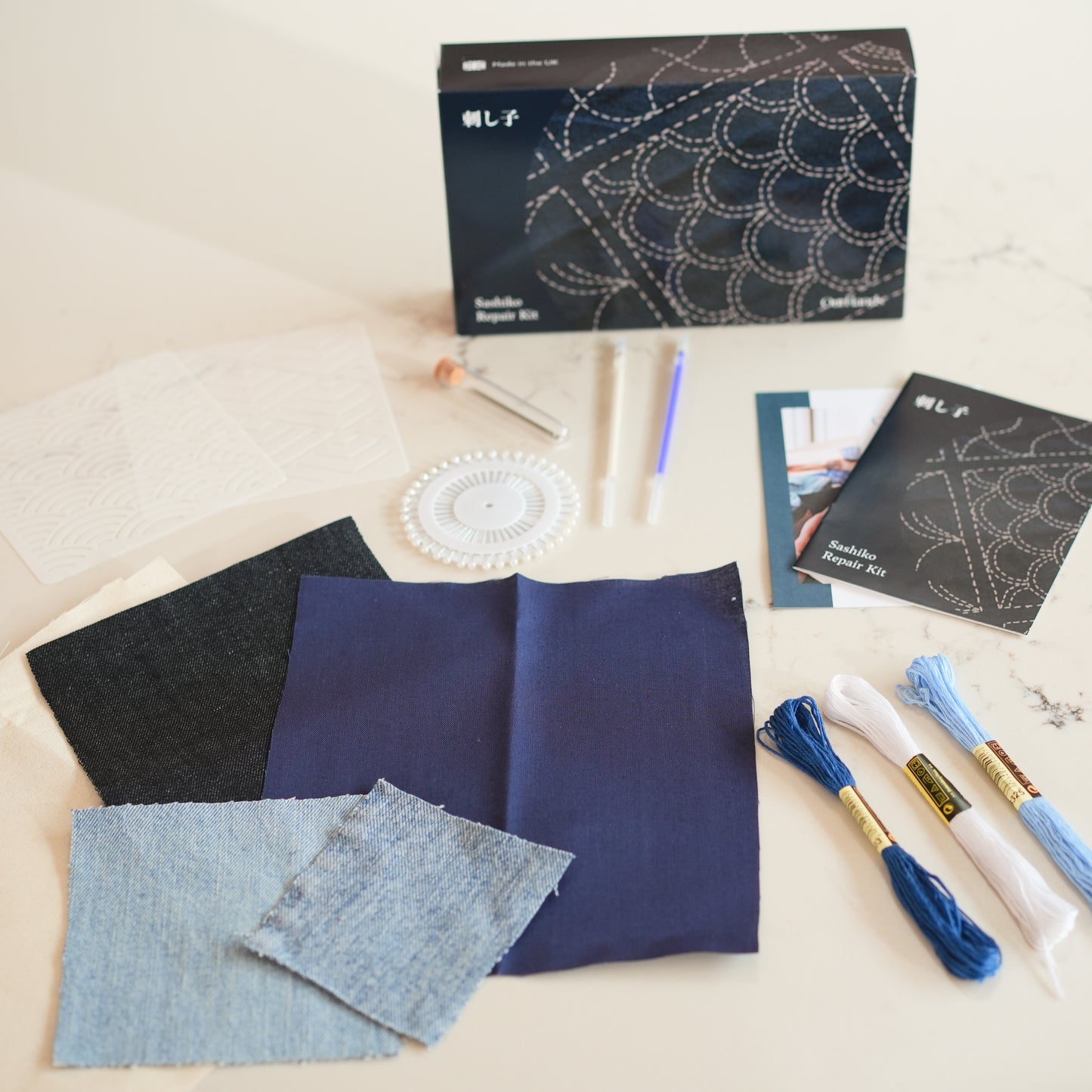

Sashiko uses the same concept to repair items of clothing. Also known as ‘visible mending’, it allows the artist to sew beautiful patterns onto garments in order to repair torn fabric. Not only does this strengthen the clothes and makes them less likely to tear, but it is also a beautiful fashion statement that has been seen on catwalks all over the world.

Wabi-sabi also pushes forward the need for both quiet respite and a strong connection to nature.

The Japanese tea ceremony, for instance, is a time of deliberate slowness and meditation. It is both dignified and humble in front of the power of nature and time, without the need for stress or intricate ornaments.

Likewise, Japanese gardens reject artificial decorations and perfectly trimmed plants. Instead, they focus on water and natural growth to symbolise the aesthetic and philosophical ideas. A walk through a Japanese garden is meant to make you forget about the outside world and your fast-paced daily life, to make you find beauty in the quiet, unassuming yet powerful flow of nature.

How to practise wabi-sabi

Wabi-sabi is a broad concept and it can be difficult to grasp. There are an infinite amount of ways to practice it.

In your daily life, it can simply be the fact of recognising that time will pass and things will change. Instead of worrying about it and carrying the weight of the world on your shoulders, you can appreciate the flow of time. Good times will pass, but so will bad times.

You can also give yourself permission to stop striving for perfection. Instead, strive for action. Accepting that nothing is perfect will let you try things that you might not have dared before! A badly-executed painting might not fit your idea of perfection, but there is beauty to be found in its simple existence.

If you are interested in the concept of wabi-sabi and the art of sashiko, you may like to give our Sashiko Repair Kit a try. It will teach you more about the art form and its technique so you can start mending and embellishing your own clothes in no time. Sustainable and mindful, it will let you express your artistic ideas without the stress of failure. After all, imperfection is the goal!